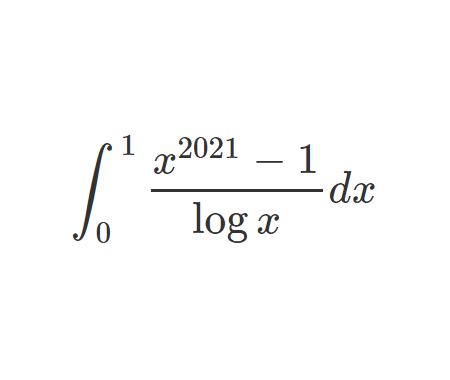

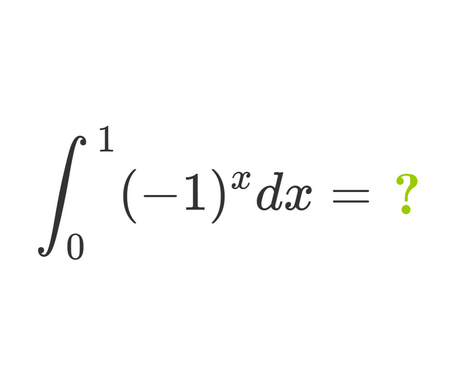

Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

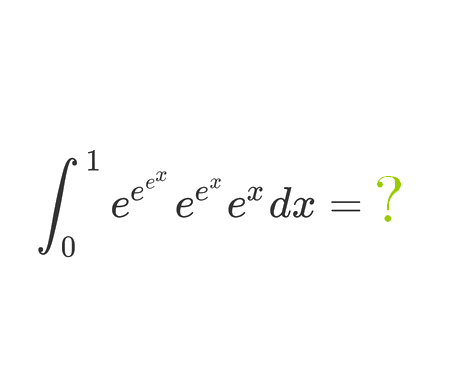

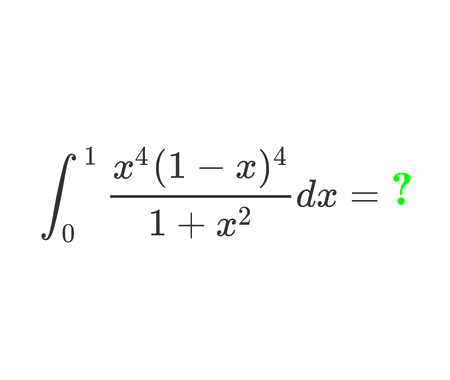

Solution

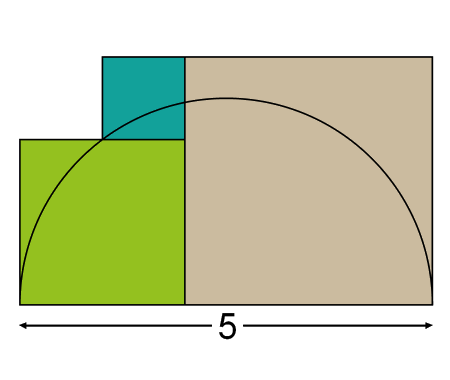

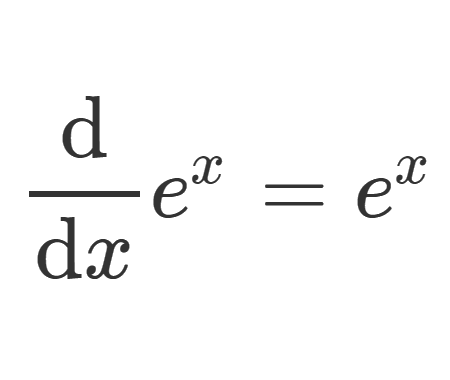

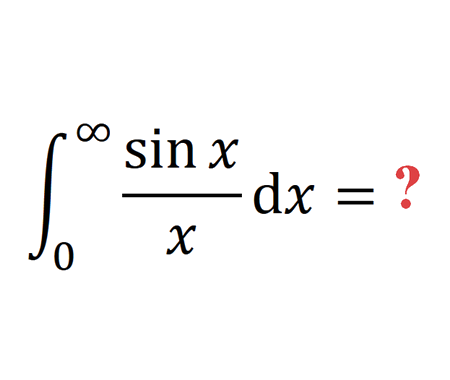

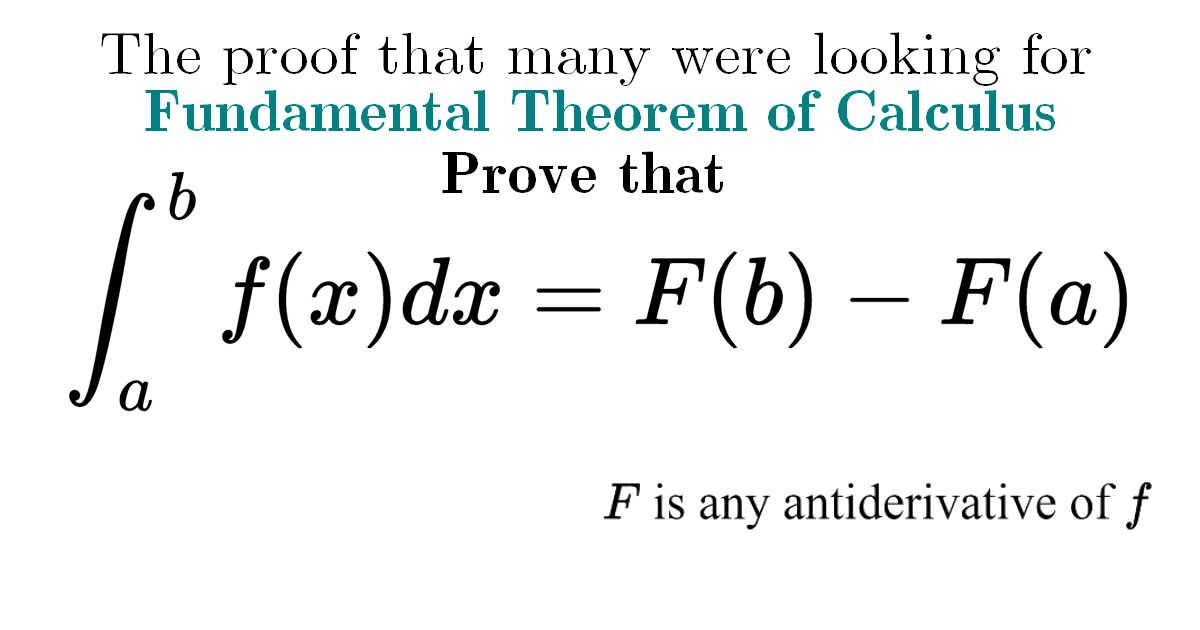

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus is one of the most important results in calculus: it establishes a deep connection between differentiation and integration. :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

There are two key parts:

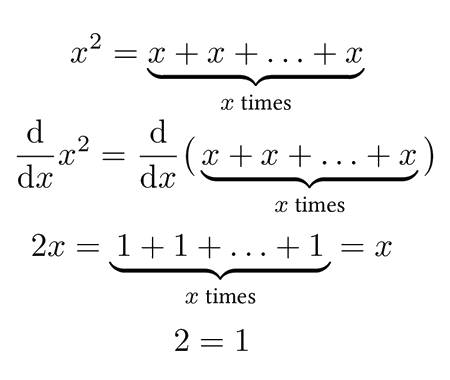

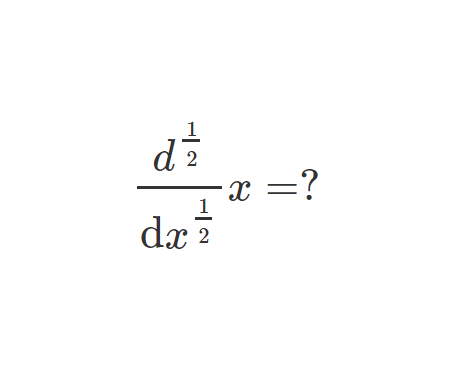

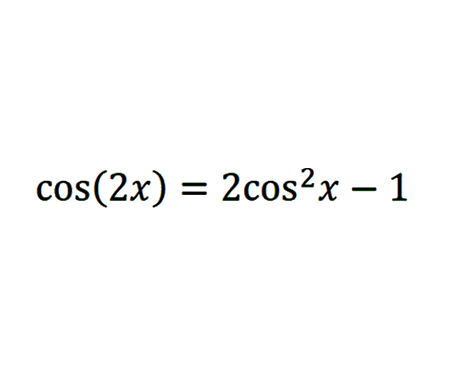

- Part 1: If \(f\) is continuous, then the derivative of its integral from \(a\) to \(x\) equals \(f(x)\). :contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

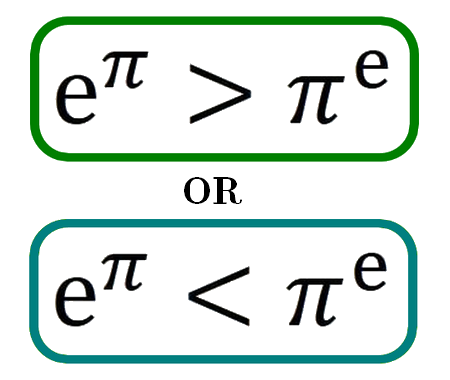

- Part 2: The definite integral of \(f\) from \(a\) to \(b\) can be computed as \(F(b) – F(a)\), where \(F\) is any antiderivative of \(f\). :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

In this solution, we will go through both parts, show how they are proven (intuitively), and apply them to compute a definite integral efficiently.

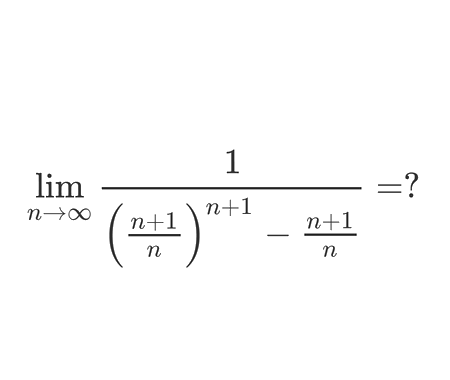

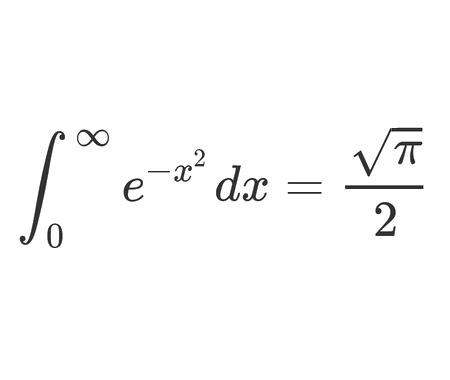

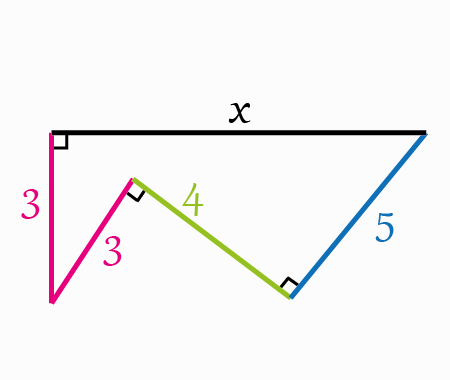

Applying the Mean Value Theorem on each subinterval \(\left[x_{i-1}, x_i\right]\) we obtain \(t_i \in\left[x_{i-1}, x_i\right]\) such that \(F^{\prime}\left(t_i\right)=\frac{F\left(x_i\right)-F\left(x_{i-1}\right)}{x_i-x_{i-1}}\) or \(F\left(x_i\right)-F\left(x_{i-1}\right)=F^{\prime}\left(t_i\right)\left(x_i-x_{i-1}\right)\). Since \(F\) is an antiderivative of \(f\), \(F^{\prime}(x)=f(x)\). Also, using the notation of the previous sections, \(x_i-x_{i-1}=\Delta x\) thus we have

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus shows that integration and differentiation are inverse operations.

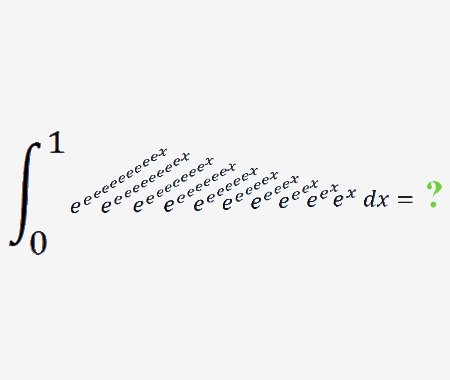

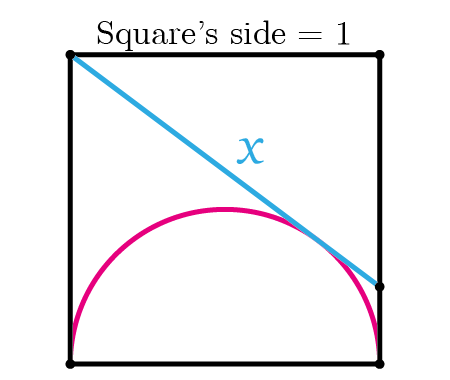

Using Part 1, we understand that the derivative of an integral (with a variable upper limit) recovers the original function.

With Part 2, we gain a powerful practical tool: instead of summing infinitely many small areas (Riemann sums), we can simply evaluate an antiderivative at the bounds.

This theorem is foundational in mathematics because it unifies two core ideas and makes the computation of definite integrals both rigorous and efficient.